Fátima Victoria, La Cazadora de Microbios de Camino

Por Isaac Pérez

17 Diciembre 2024

El poder encontrar y entender mundos invisibles a nuestro alrededor es una posibilidad ha fascinado a la humanidad desde tiempos antiguos. De Platón a Pasteur, el afán por explorar estos mundos que trascienden la simple vista ha sido un potente motor en la ciencia.

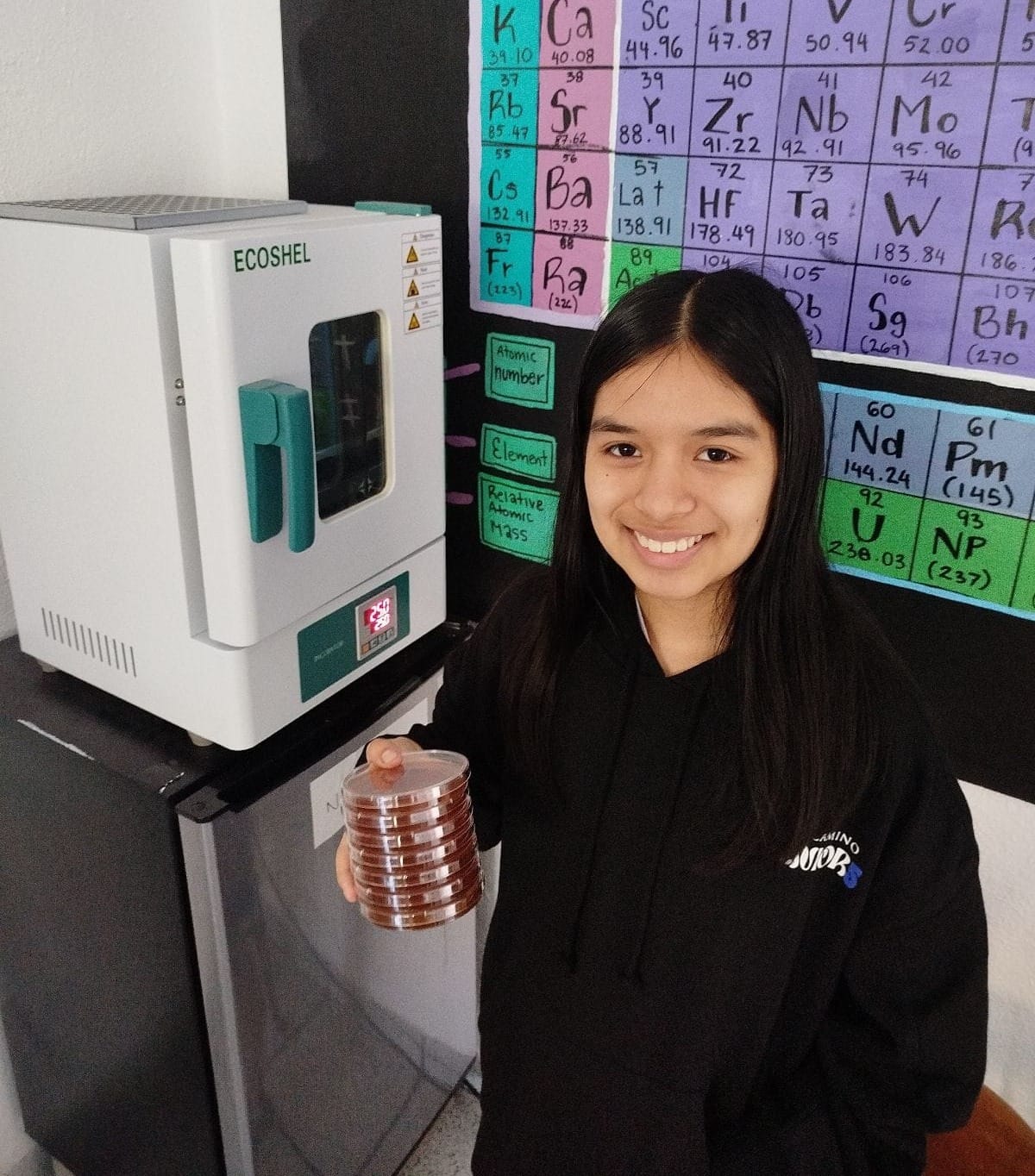

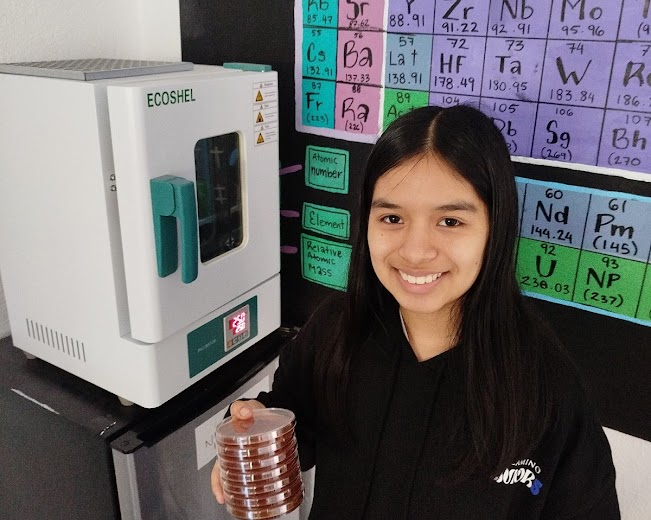

En el Camino, Fátima Victoria, alumna de 12° grado, se une a estos exploradores a través de su monografía en Biología, con la cual busca iluminar áreas aún poco entendidas del mundo microscópico.

“Está adentrándose en un campo relativamente nuevo”, dice nuestro profesor de biología de Preparatoria, Mr. Hugo Campos. “La verdad es algo también nuevo para mí, yo no lo vi en la carrera”, aclara.

Aunque aún no entra a la universidad, Fátima está realizando por sí misma una investigación microbiológica en nuestro laboratorio con respecto a un tipo de bacterias llamadas “endófitas”, las cuales viven en tejidos de plantas, tales como sus raíces, tallos u hojas.

La monografía, una investigación académica formal, forma parte de los requisitos del Programa de Diploma y es algo que todos los alumnos en El Camino deben realizar. Para Fátima, esta fue una oportunidad de aprender más acerca de un tema que picó genuinamente su interés.

“Me pareció bastante interesante cómo, al igual que la microbiota de los humanos, las plantas tienen algo similar y que estas bacterias fueran benéficas”, dijo Fátima.

“Microbiota” es como los científicos llaman hoy en día a la diversidad de bacterias y otros microbios que habitan dentro de organismos más grandes, como en la piel o en el sistema digestivo de los seres humanos.

“De hecho es una tendencia actual, gran parte de lo que ya se sabe en animales, ahora se está descubriendo que las plantas también lo tienen”, agrega Mr. Hugo. “Durante muchísimo tiempo se satanizó a las bacterias, y no es cierto”.

Las bacterias endófitas con las que trabajará Fátima buscan tener un impacto benéfico, cuyas aplicaciones pueden ayudar en la agricultura y la jardinería orgánicas.

“Esto va un poco en contra de la concepción que tenemos de las bacterias, ya que usualmente las vemos como organismos patógenos o que causan enfermedades”, dice Fátima.

Específicamente, Fátima busca entender cómo pueden utilizarse bacterias que viven en el tejido de las pencas de nopal (Opuntia ficus-indica) para mejorar la germinación y el crecimiento de las plantas de maíz.

Para su estudio, Fátima desarrolló un método tomando como base otros estudios ya publicados en artículos de investigación, y apoyándose con el Profesor Hugo Campos, así como Miss Yamillet Castro, encargada de laboratorio, y el Profesor Iván Quintana, nuestro profesor de Química.

El método consiste en esterilizar la parte externa de la penca del nopal, ya que esta podría contener bacterias del medio ambiente. Una vez hecho esto, el nopal se licúa con agua esterilizada y este puré después es separado entre sus componentes líquidos y sólidos usando una máquina especial que le da vueltas como una lavadora, llamada una “centrífuga”. La parte más líquida ahora contiene las bacterias que estaban dentro de la penca.

Este líquido se aplica entonces a placas de petri, que son unos discos de plástico que contienen una gelatina especial llamada “agar”, de la cual se alimentan las bacterias y que permite que se multipliquen en cantidades que sean fácilmente observables e identificables.

Una vez cultivadas las bacterias, estas se disuelven en solución salina para crear una “solución bacteriana”, que se aplicará a semillas de maíz para poder estudiar su efecto en cómo éstas germinan y las plantas que crecen cuando hay estas bacterias presentes.

“La principal hipótesis que también se ha visto en otras investigaciones similares es que las bacterias tienen un efecto benéfico en el crecimiento de las plantas”, dice Fátima.

En los últimos años, estudios conducidos por investigadores de varias universidades en Estados Unidos, Brazil y Europa han aplicado técnicas similares a las que propone Fátima, obteniendo buenos resultados como protección contra enfermedades y la producción de hormonas que promueven el crecimiento de plantas como la soya y el sorgo.

Dichos resultados inspiraron a Fátima a probar el impacto de bacterias en plantas con aplicaciones en nuestro contexto Mexicano, el nopal y el maíz.

“Eso se observaría como en una planta como más alta, más densa y el porcentaje de germinación de las plantas y también estoy investigando la longitud de la raíz y de la planta”, dice.

De tener éxito, el potencial del estudio de Fátima podría tener gran impacto a futuro de acuerdo con Mr. Hugo.

“Yo lo primero que llegué a imaginarme es como una nueva técnica de cultivo, de poner plantas apostándole a lo orgánico, no utilizando sustancias químicas, agroquímicos, sino un tratamiento biológico que haga que las semillas puedan estabilizarse mejor y tener mejores cosechas, vaya, toda la implicación que esto podría tener, esa es la parte que ella está vislumbrando,” dijo.

A pesar de esta gran promesa, no obstante no todo ha sido fácil.

“Lo que está viendo es que está desarrollando técnicas de preparación de medios, la necesidad de contar con equipos. Se está imaginando cosas del doctorado”, dice con cierta nota de humor Mr. Hugo.

“Está aprendiendo a lidiar con la frustración del científico”, agrega. “Lo que vemos en el artículo, no es tan fácil de replicar, porque no tenemos los mismos medios. Ella cree que lo que leyó en el artículo, lo va a poder replicar sin problemas, pero le hago ver que lo que ella ve en el artículo fue un proceso de años para que pudiera publicarse, y que obviamente tiene que lidiar con eso.”

A pesar de los retos, Fátima lleva a cabo su investigación con empeño y resiliencia, y una buena dosis de solidaridad de la comunidad.

Este año, el Colegio adquirió la incubadora profesional que Fátima está utilizando para su estudio, una mejora por sobre la pequeña incubadora con la que una ex-alumna realizó la primera investigación microbiológica llevada a cabo en nuestro programa de Diploma hace dos años.

“Alessa [Carbó] hizo eso, después Connie [Tocino] y Ángela [Hernández] también le apostaron a microbiología, ahora es Fátima, y hay otros que también están pensándole, no como tal con bacterias, pero sí levaduras, sí otras cosas hacia la parte del estudio de microorganismos”, dice Mr. Hugo.

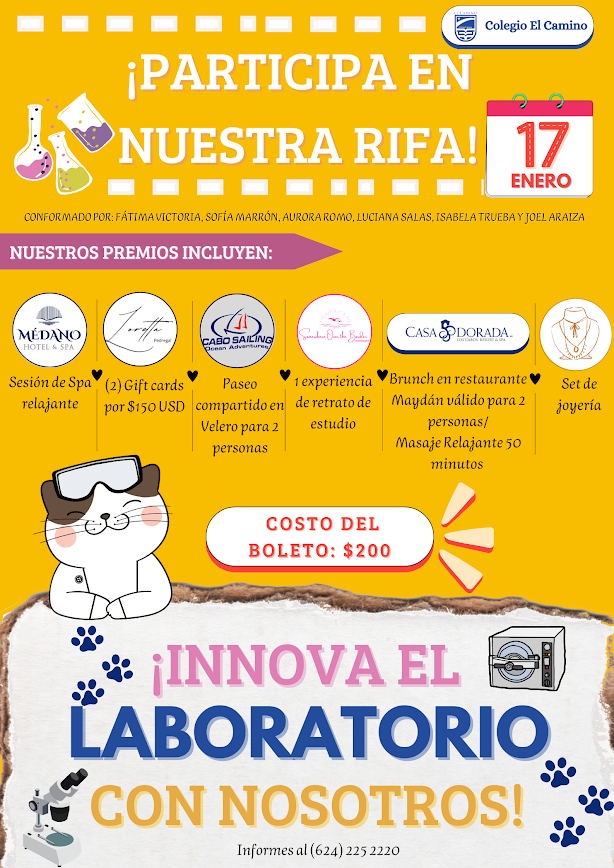

Como parte de su componente de Servicio en CAS, otro requisito del Programa de Diploma, Fátima ahora organiza una rifa junto con el club Camino Verde para continuar adquiriendo equipamiento nuevo para nuestro laboratorio, con el que futuros estudiantes podrán realizar investigaciones más avanzadas.

La rifa, la cual se llevará a cabo en este mes y enero de 2025, está abierta a cualquier persona que quiera beneficiar a la investigación científica en nuestro colegio. Los premios incluyen paquetes de spa, comidas en restaurantes de lujo y otros beneficios donados por padres de familia de la comunidad de El Camino. Los boletos tendrán un precio de $200 MX.

“Yo quiero, que los chicos de las siguientes generaciones vayan y sepan qué es lo que están haciendo, yo hago mi labor mostrándoles lo que hicieron las generaciones anteriores, y que vean las posibilidades”, dijo Mr. Hugo.

Con su investigación y recaudando fondos para nuestro laboratorio, Fátima aporta a un creciente legado de investigación microbiológica en el Colegio y se prepara para una futura carrera en Biotecnología, carrera a la cual está aplicando en universidades nacionales y del extranjero.

“Me gustaría pensar que puedo continuar haciendo este tipo de proyectos en un futuro, espero más especializados”, concluye.

Fatima Victoria, El Camino Microbe Hunter

By Isaac Pérez

17 December 2024

Being able to find and understand invisible worlds around us is a possibility that has fascinated mankind since ancient times. From Plato to Pasteur, the human urge to explore these worlds beyond the reach of the naked eye has been a powerful driving force in science.

At El Camino, Fátima Victoria, a 12th grader, joins these explorers thanks to her Extended Essay in Biology, with which she seeks to learn more about little understood facets of the microscopic world.

“She is delving into a relatively new field,” says our high school biology teacher, Mr. Hugo Campos.

“It's actually something new to me too, I didn't see it myself in university,” he clarifies.

Although she is not yet in college, Fatima is conducting her own microbiological research in our lab, on a type of bacteria called “endophytes,” which live in plant tissues, such as roots, stems or leaves.

The Extended Essay, a formal academic investigation, is part of the requirements of the Diploma Program and something that all students at El Camino are required to do. Fátima saw this as an opportunity to learn more about a topic that genuinely piqued her interest.

“I found it quite interesting how, just like the microbiota of humans, plants have something similar and that these bacteria were beneficial,” Fátima said.

Microbiota is what scientists today call the diversity of bacteria and other microbes that live inside larger organisms, such as on the skin or in the digestive system of humans.

“In fact it is a current trend, much of what is already known in animals is now being discovered in plants as well,” adds Mr. Hugo.

“For a very, very long time bacteria were demonized, and it's not true.”In fact, the endophytic bacteria that Fatima will be working with could actually have a beneficial impact, with applications that can help in organic farming and gardening.

“This goes a bit against the conception we have of bacteria, as we usually see them as disease-causing organisms,” says Fátima.

Specifically, she seeks to understand how bacteria living in the tissue of prickly pear cactus (“nopales”) (Opuntia ficus-indica) stalks can be used to improve the germination and growth of corn plants.

For her study, Fatima developed a method based on other studies already published in research articles, with the support of Professor Hugo Campos, as well as Miss Yamillet Castro, our lab attendant, and Mr. Ivan Quintana, our Chemistry teacher.

The method consists of sterilizing the external part of the nopal stem, since it could contain bacteria from the environment. Once this is done, the nopal is liquefied with sterilized water and this puree is then separated into its liquid and solid components using a special machine that spins it around like a washing machine, called a “centrifuge”. The more liquid part now contains the bacteria that were inside the stalk.

This liquid is then applied to petri dishes, which are plastic disks containing a special gelatin called “agar,” on which the bacteria feed and which allows them to multiply in quantities that are easily observable and identifiable.

Once the bacteria are cultured, they are dissolved in saline to create a “bacterial solution,” which will be applied to corn seeds in order to study their effect on how plants germinate and grow when these bacteria are present.

“The main hypothesis that has also been seen in other similar research is that bacteria have a beneficial effect on plant growth and germination rates,” Fatima says.

In recent years, studies conducted by researchers from several universities in the United States, Brazil and Europe have applied techniques similar to those Fátima proposes, obtaining good results such as protection against diseases and stimulating hormones that promote the growth of plants such as soybeans and millet.

Those results inspired Fátima to test the impact of bacteria on plants with applications in our Mexican context, nopal cacti and corn.

“The results would be observed in plants that are taller, denser and with a higher germination percentage of the seeds, and I am also investigating root and plant length,” she says.

If successful, the potential of Fátima's study could have great impact down the road according to Mr. Hugo.

“The first thing I thought of was using it for a new cultivation technique, betting on organics, not using agrochemicals, but biological treatments instead, which make for more stable seeds and better crops – all the implications that this could have, that's the part she is envisioning,” he said.

Despite the great promise in Fátima’s study, however, it hasn't all been easy.“She's coming up with media preparation techniques, she's seeing the need for equipment; she's basically figuring out Ph.D. stuff,” Mr. Hugo says with a note of humor.

“She's learning to deal with the same frustration scientists live with,” he adds.

“What we see in the article it's not so easy to replicate, because we don't have the same means. She thinks that whatever she read in the article, she will be be able to replicate it without problems, but I try to make her see that what she saw in the article entailed a process of years before it could be published, and she obviously has to deal with that.”

Despite the challenges, Fátima carries on her research with determination and resilience, and receives a good dose of solidarity from our community.

This year, Camino purchased the professional incubator Fátima is using for her study, an upgrade over the small incubator with which a former student carried out the first microbiology study conducted in our Diploma program two years ago.

“Alessa [Carbó] did that, then Connie [Tocino] and Ángela [Hernández] also bet on microbiology, now it is Fatima, and there are others who are also thinking, not as such with bacteria, but yeast, yes other things towards the part of the study of microorganisms,” says Mr. Hugo.

As part of her CAS component, another requirement of the Diploma Program, Fátima is now organizing a raffle along with students from the Camino Verde club to help acquire new equipment for our lab, with which future students will be able to conduct more advanced research.

The raffle, which will take place this month and January 2025, is open to anyone who wants to support scientific research at our school. Prizes include spa packages, meals at fine restaurants and other benefits donated by parents in the El Camino community. Tickets will be priced at $200 MX.

“I want the kids of the next generation to go and know what Fátima and others are doing, I do my part by showing them what the previous generations did, and let them see the possibilities,” said Mr. Hugo.

With her research and raising funds for our lab, Fatima contributes to a growing legacy of microbiology research at the College and is also preparing for a future career in Biotechnology, for which she is applying to universities nationally and abroad.

“I would like to think that I can continue to do these types of projects in the future, hopefully more specialized ones,” she concludes.